Dennis Rodkin

Crain’s Chicago Business

February 22, 2023

The Rev. James Meeks

When he announced his retirement from the pulpit of his 10,000-seat church on 114th Street in January, the Rev. James Meeks told the congregation how he plans to spend his retirement years: building homes in the neighborhood.

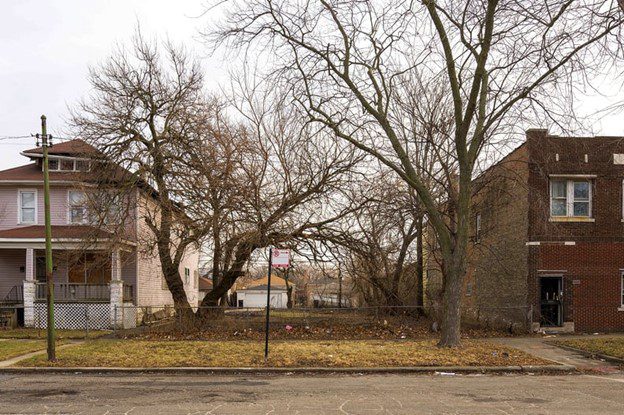

A few weeks later, as Meeks stood on the corner of 118th Street and Indiana Avenue in Chicago’s Roseland neighborhood, where he expects to break ground on the first 20 homes this spring, he said it’s not so much a retirement project as an extension of the work he’s been doing for four decades.

“I’ve always thought that a church that didn’t come outside its four walls to build its community isn’t worth its salt,” said Meeks, the 66-year-old pastor emeritus of Salem Baptist Church and a former Illinois state senator.

In a long-disinvested neighborhood, revitalization is an uphill battle, fraught with obstacles like financing, high crime, the stability of homeowners who convert from renting and, according to Meeks, “skepticism.” Looking around the blocks on his project map, many of them gap-toothed with vacant lots, it’s difficult to picture the change he foresees.

If Meeks can fill dozens of long-vacant lots with new houses and homeowners, “that will have a substantial, positive impact on the area,” said Erik Doersching, CEO of Tracy Cross & Associates, a Schaumburg-based consultancy to the homebuilding business.

Roseland could begin to revitalize with clusters of new homes attracting people who “will speak up about crime (and) won’t put up with it,” says Vernon Lilly, who’s been selling real estate in the area for four decades. “If they’re living in clusters of new homes, they’re going to say they want police protection, they want the neighborhood going their way.”

Meeks’ primary adviser in the project, David Doig, president of Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives, sees the proposed new homes as coming at the right time, ahead of the Chicago Transit Authority’s planned Red Line extension to 130th Street. One proposed stop is at 115th Street and Michigan Avenue, a few blocks from the first round of new homes. A direct transit line to neighborhoods north of Roseland and to the Loop could enhance the neighborhood’s appeal to homebuyers.

“One of the big demand drivers here is going to be the new Red Line,” Doig said.

Best known for its multi-pronged, $350 million Pullman revitalization effort, CNI is partnering with Meeks’ three-year-old Hope Center Foundation. Doig said construction costs for the Meeks initiative will be covered through a revolving fund Doig’s group has raised with contributions from BMO Harris, Chase Bank and others.

“We’re trying to build the fund to $25 million,” Doig says, “but right now, we have $12 million.” The fund is for both the Meeks program on the South Side and a similar homebuilding effiort by Lawndale Christian Development Corporation and United Power for Action & Justice on the West Side.

New homes for Roseland

The first houses to be built by the Rev. James Meeks’ Hope Center Foundation and its partner, Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives, will be on vacant lots that Salem Baptist Church owns on the blocks near its former sanctuary at 118th Street and Indiana Avenue. The congregation now worships at House of Hope, seen in the inset and built in 2005.

The funding is more than sufficient to build the first 20 homes, Doig said, and when they’re sold, the money replenishes for additional construction. Shenita Muse, executive director of the Hope Center Foundation, said she has buyers lined up for at least four homes, and expects to have more as the foundation’s homeownership training classes progress.

The three-bedroom, two-bath houses will be priced from $200,000 to $210,000, Muse says, but buyers will pay about $30,000 less because of down payment incentives and other grants the foundation has lined up from housing agencies and donors.

Buyers will be primarily former renters who’ve been through the foundation’s classes and learned how to maintain and pay for a house. Training and financial guidance continue after the family moves in, and some financial incentives only kick in when the buyers have been in the home for five years.

“This whole thing would be a failure if people are rotating in and out of these houses,” Meeks says.

Housing has long been part of Meeks’ community-building agenda. A dozen years ago, when running for mayor, he pushed for programs that would convert foreclosed buildings into low-income housing. It’s only now in retirement, he said, that “I have time to take this on” at the scale he’s got in mind.

In his retirement address from the pulpit in early January, Meeks said his goal was to build 1,000 homes. In a later interview, he suggested that’s more of an ideal, a shiny target to aim for.

Ald. Anthony Beale, whose 9th Ward encompasses the Meeks project area, said the stated goal of “1,000 houses is extremely aggressive and ambitious, but we definitely have enough vacant lots to do it.”

If Meeks can fill dozens of long-vacant lots with new houses and homeowners, “that will have a substantial, positive impact on the area,” said Erik Doersching, CEO of Tracy Cross & Associates, a Schaumburg-based consultancy to the homebuilding business.

On a map of about 12 square blocks between 116th and 119th streets, between Michigan and Prairie avenues, the project map shows dozens of targeted lots. They’re in various hands now, owned by Salem Baptist, the city, the Cook County Land Bank Authority or private owners. On the block where the spring groundbreaking will be held, 10 of 22 lots are targets for new houses.

Doersching’s firm, Tracy Cross, is not connected to Meeks’ project. But when evaluating a comparable neighborhood in another Midwestern city, which he declined to name, for a client looking to build low-cost homes, Doersching says, “we found there was significant demand for homes (built by) a local organization that has been there in the neighborhood.”

Building houses in clusters is fundamental, Doig says. “Filling up those vacant lots with families who take ownership of the block is the best crime-fighting strategy,” he says, citing a significant drop in crime around a previous project of dozens of homes built near St. Bernard Hospital in Englewood.

Meeks grew up in Englewood, the fourth child of parents who came up from Mississippi in the Great Migration. After a few years in Bronzeville, his parents bought a two-flat at 64th and Laflin streets.

At age 24, Meeks became pastor of Beth Eden Baptist Church in Morgan Park, and at 29, he founded Salem Baptist. With his wife, Jamell Meeks, he raised four children. The couple live in Roseland.

Building homes is not Meeks’ only retirement plan. He says he also wants to golf and mentor younger pastors, but that the housing program is “my focus, the best thing to get up for every morning.”