Most of the local industry got caught flat-footed in 2020, with little product in the pipeline because sales had been dismal for a decade.

Dennis Rodkin

Crain’s Chicago Business

October 19, 2022

Erik Doersching is CEO of Tracy Cross Associates, a consultant to the homebuilding industry.

A couple of years ago, a national homebuilder exited the long-sluggish Chicago market, selling its 232 suburban lots to another firm and telling Crain’s it wasn’t coming back.

For the buyer of those lots, M/I Homes, it was like kismet. Mere weeks later, COVID supercharged homebuilding around Chicago and nationwide as homebound Americans sought more living space.

Of course “we didn’t see the pandemic coming,” says Rick Champine, Chicago-area president of Ohio-based M/I Homes, but with all those newly acquired lots, “we were ready to grow” with the housing boom that COVID and low interest rates delivered.

Business shot up about 60% as M/I sold 668 Chicago-area homes in 2021, according to Tracy Cross Associates, a consultant to the homebuilding industry based in Schaumburg. Compared with 2019 sales, that’s an increase of 251—or more than all the inventory M/I took off Arizona-based Taylor Morrison’s hands in February 2020, on the eve of the boom.

While that timely acquisition juiced up M/I, most of the local homebuilding industry got caught flat-footed in 2020, with little product in the pipeline because sales had been dismal for a decade. And then the boom subsided this summer, as the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates to slow inflation. The boom lasted about two years, which is less time than it takes builders to roll out new product.

In other words, the boom was too short and shallow to lift Chicago’s homebuilding industry out of the trough it’s been in since the housing bust of the 2000s. New-home permits in metropolitan Chicago rose 20% between 2020 and 2022, according to the St. Louis Fed, lagging a 36% national surge and well behind increases in fast-growing cities around the country.

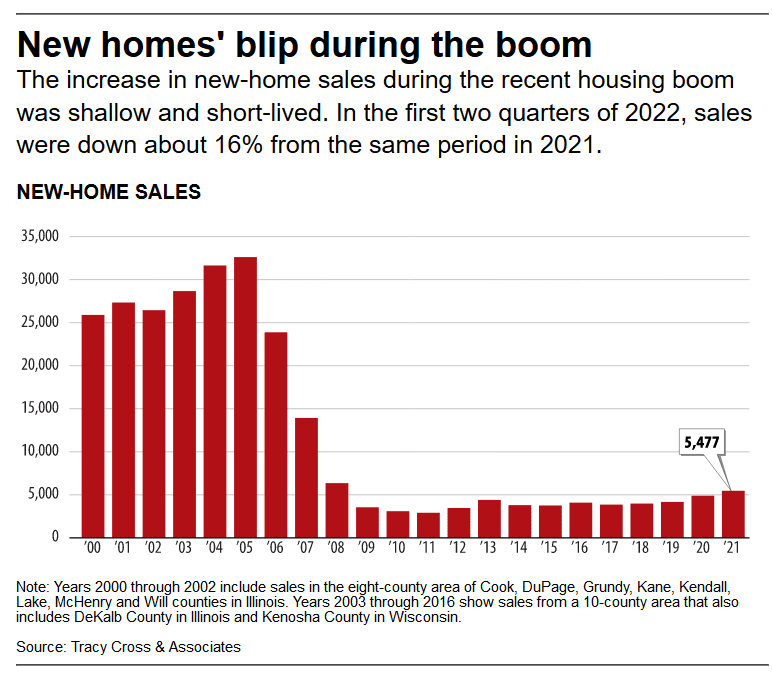

Before the pandemic, new-home sales “were 90% below the peak” of the early 2000s says Erik Doersching, CEO of Tracy Cross. “We’re still 70% below the peak. It was more like a blip than a boom. But it was a nice blip.”

In 2021, homebuilders sold more newly built homes than in any year since 2008, at prices that were up about 19% from 2020. But by 2022, inventory dwindled and so did sales, dropping nearly 16% in the first half of the year. Doersching expects third-quarter figures due later this month to show that the blip is well and truly over.

The takeaway is sobering for Chicago-area homebuilders and the regional economy. Local builders and their subcontractors and suppliers have largely failed to benefit from their industry’s first significant upturn in more than a decade. And residential construction, a major contributor to the local economy for generations, isn’t the growth engine and job creator it once was.

At bottom, the long-term weakness of Chicago-area homebuilding reflects the area’s slow population growth and related loss of luster among major U.S. job markets—and in itself constricts one particular type of job, skilled construction labor.

The good news for builders: There’s not likely to be a big overhang of unsold homes.

“We didn’t have time to get out over our skis,” says Charlie Murphy, president and CEO of Icon Building Group, based in Vernon Hills. “We got out over the first few buckles on our boots.”

As demand rose, Murphy took on new hires, growing from 13 employees at the start of the pandemic to 27 now. “There was a time when I was adding them two at a time,” he says.

While rising interest rates slowed foot traffic at some of his developments, Murphy says he doesn’t foresee job cuts at the moment. That’s because Icon specializes in semi-custom homes that sell in the over-$700,000 range, where move-up buyers aren’t as sensitive to rising interest rates as first-time and under-$400,000 buyers.

Neither M/I nor Icon has started cutting prices, their principals say. But the trimming has started at Lennar, based in Miami and the biggest-volume builder in Chicago, with 593 homes sold in the second quarter. In a late-September earnings call, CEO Rick Beckwitt included Chicago in a list of 22 markets nationwide where, he said, “we’ve had to offer more aggressive financing (programs), base price reductions and increased incentives to regain sales momentum.”

Builders Murphy and Champine both said a key factor that restrained them from overbuilding is that they’re clear-eyed veterans of Chicago’s new-home market. “I’ve been in this business for 31 years and Chicago for 20,” Champine said. “You’re dealing with a metro of 9.5 million people that is selling (less than) 6,000 homes a year, where in other cities they’re selling triple that. That holds (supply) down.”

One reason we’ve been building below capacity for years is that Chicago has had some of the slowest-rising home values among big US cities. While the comparative affordability of homes is an economic plus for Chicago, it also eliminates the incentive of builders to create cheaper alternatives to existing housing stock.

Another negative behind the lower prices: flat or declining population figures that suppress demand. “Growth creates demand for new housing units,” says Robert Dietz, chief economist for the National Association of Home Builders. “Illinois has one of the lowest (numbers of) single-family homes built per capita in the country.”

Dietz says higher labor costs and heavier regulation also help slow building here. “A highly regulated market like Chicago was challenged. It takes longer to develop land there, the taxes and fees are higher, and population growth isn’t there pushing demand. It created a vicious cycle where it’s hard to build, so not much had been building,” which meant the voracious appetite for homes spurred by COVID-19 was funneled to the existing-home market.

Champine cites another factor in Chicago builders’ slower response time. Because of the long building drought, the pool of skilled laborers has shrunk. On top of that, supply chain issues slowed all markets.

Meanwhile, Dietz says, “there were plenty of smaller markets where building accelerated with demand.” For example, data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis shows permits for new private housing grew 115% in Indianapolis between March 2020 and March 2022, and 177% in Wilmington, N.C., dwarfing Chicago’s 20% increase.